Software Testing vs. Software Inspection

|

|

The aspects of software quality in an increasingly digital world have become one of the major distinguishing factors of a successful and a failing system. Software is important to the operations of modern businesses, governments, and even consumers. Maintaining software quality has many advantages, such as customer satisfaction, boosting productivity, etc. As software delivery has undergone agile and DevOps cultures, the rapidity of the process has escalated significantly. In this respect, organizations tend to embrace a multi-layered approach to quality assurance, which implies the combination of both static (e.g., inspection) and dynamic (e.g., testing) methods to cover it extensively.

| Key Takeaways: |

|---|

|

Understanding Software Testing and Inspection

Software testing and software inspection are two of the main methods employed at various stages of the SDLC that can be used to provide quality and correctness of the produced product. Software inspection is a form of static analysis of software artifacts and includes the manual procedure of reviewing requirements, design documents, source code, and test plans and does not involve actually running the code. Read: How Requirement Reviews Improve Your Testing Strategy.

Software testing is an active method of validation because it entails running the program in controlled environments to actuate the flaws in it. It is generally followed once the code has been produced, and it incorporates the different levels that entail unit, integration, system, and acceptance tests. It is important to test in order to find out run-time errors such as crashes, faulty results, memory leakages and interface mismatch.

Let’s look into both in detail.

Software Testing Concepts and Approaches

Software testing is a very crucial stage in the software development life cycle (SDLC), which makes a software product match its intended needs. This also makes it reliable in every predictable circumstance. Unlike passive quality assurance techniques, testing is an active process that runs real code with real data to verify and validate functionality. It goes beyond simple bug detection to ensure reliability, security, usability, and compliance. It is especially critical in industries like healthcare, finance, and automotive, where failures can have catastrophic consequences. Well-planned and documented testing also builds trust in the product’s quality, reduces business risks, and provides valuable insights for release planning and risk acceptance. With modern practices like automation and CI/CD pipelines, testing accelerates feedback loops, increases efficiency, and enables continuous delivery of stable software.

Key Points of Software Testing:

- Verification and Validation: Ensures the software is built correctly (verification) and meets user and business needs (validation). Read more: Verification and Validation in Software Testing: Key Differences.

- Risk Mitigation: Detects defects early to prevent financial, legal, or safety risks. Read more: Risk-based Testing: A Strategic Approach to QA.

- Quality Metrics: Measures attributes like accuracy, efficiency, exhaustiveness, and compliance with standards. Read: Essential QA Metrics to Improve Your Software Testing.

- Stakeholder Confidence: Provides actionable data on product readiness and supports informed release decisions.

- Modern Enablement: Automation and continuous testing enhance speed, reliability, and scalability in agile and DevOps environments.

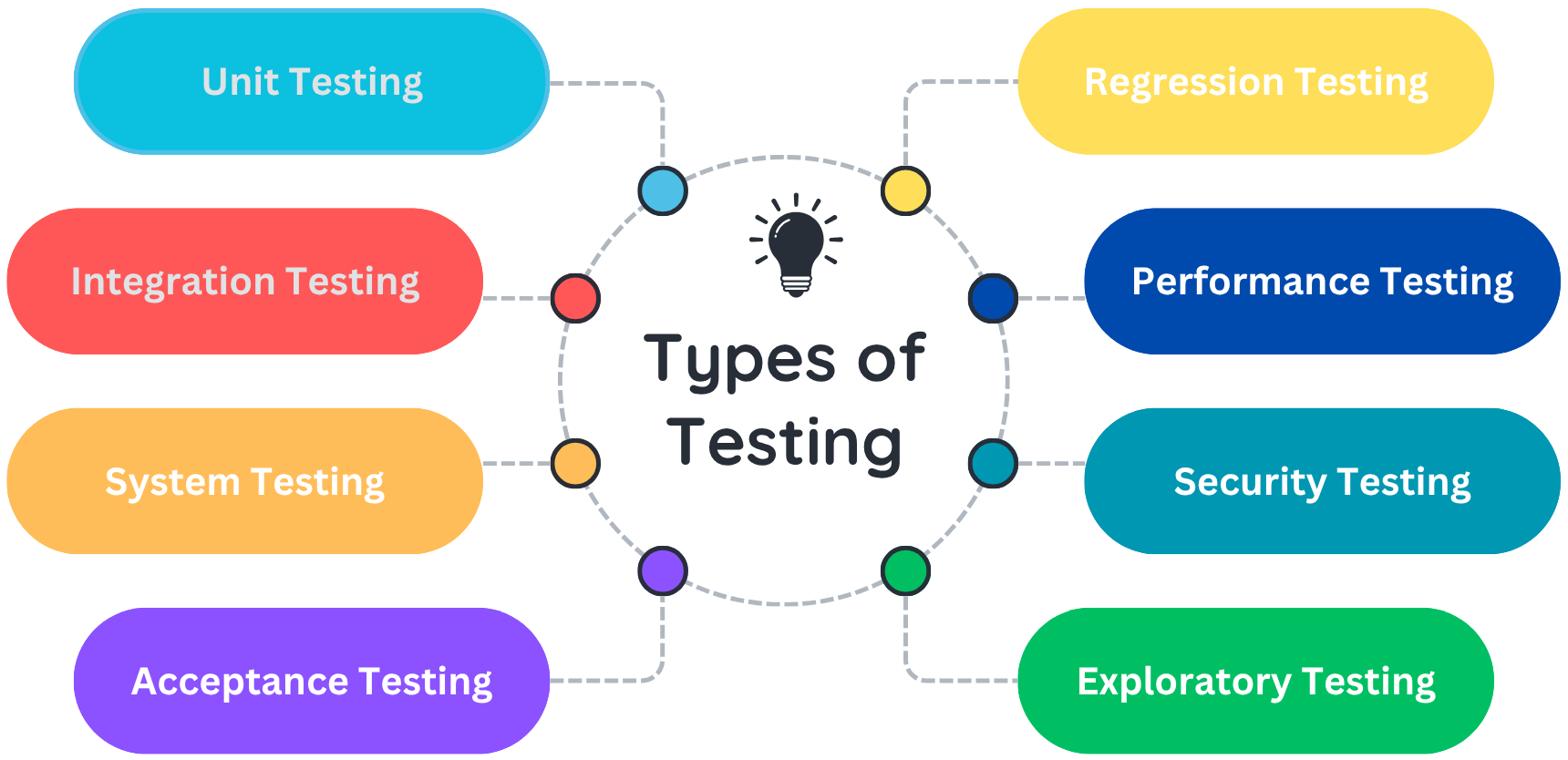

Types of Testing

We perform different types of testing across the various stages of the Software Development Life Cycle. Let’s go through each of them.

Unit Testing

Unit testing is the finest-grained tier of software testing and aims at considering what can be examined the least, the units of the program: one unit is one functionality, one method, or one class. It is usually carried out by developers when applying their code, and it makes each unit have perfect behaviour as is expected of it when separated without contact with the other parts. Such a type of testing is critical in defect identification early enough, and this way, the issues are easier and cheaper to repair.

Integration Testing

The purpose of this kind of test, namely, integration testing, is to check how various components or modules interact after each of them is checked separately. They might not have issues when each unit operates independently, but when it is time to integrate with others, such as complex applications that rely on APIs, external libraries, or third-party services, integration issues are likely to be experienced. Integration testing will ensure that data is transmitted in the right way, that dependencies are managed, and that the flow of logic between individual components is seamless.

System Testing

System testing involves an elevated level of testing that is done under higher testing conditions when the system software that has been developed is fully assembled and tested as a unit. This testing is, however, performed by third-party QA teams whose mission is to determine that the application has been functioning according to what is outlined in the requirements documentation. It is like real-world use as it validates end-to-end workflow, data handling, functional, and non-functional requirements.

Acceptance Testing

The acceptance testing is a test to check and ascertain that a system is in compliance with the business requirements and can be utilized. It is usually the last stage of testing and entails the stakeholders, the clients, or even the end users confirming that the application will work as desired in real-life situations. There are two commonly used types:

- Alpha testing is conducted internally by the development team.

- Beta testing is conducted by the external users, who test software in a real-life setting.

Regression Testing

Regression testing is carried out so that the modifications to the codebase (bug fixes, enhancements, or new functionality) do not impact the functionality that exists on the application in a negative manner. It is a requirement where the model of development is iterative (such as Agile or DevOps) and software is changed regularly.

Performance Testing

The performance testing involves tests on the extent to which the software will perform according to set workloads and usage conditions. It concentrates on response time, throughput, scalability, and utilization of resources. This kind of testing makes the application very stable and responsive even when it is in normal operating conditions. The issues with performance, if not detected, can have negative effects on user experience and the reliability of systems, particularly in high-volume or real-time systems.

Security Testing

Security testing is aimed at identifying vulnerabilities, data leakages, mishandling, and other attacks that may be carried out by malicious actors. It is especially significant in systems in which sensitive data of the user, financial information, or authentication secrets are processed. Security testing analyzes parameters such as access control, encryption, session management, input validation, and how to meet standards and regulations. Some of the popular techniques used in attack simulation to determine how resilient an application is:

- Penetration testing

- Ethical hacking

- Vulnerability scanning

Exploratory Testing

Exploratory testing is an unscripted, informal approach with testers applying their intuition, subject matter expertise, and inventiveness to their exploration of the application in order to identify flaws. As opposed to fixed test case information, testers explore the software on the fly, responding to the software’s behaviour. It is an effective process of finding latent bugs, edge cases, and usability problems not captured in the official documentation of test coverage. Learn: How to Automate Exploratory Testing with AI in testRigor.

Software Testing is of a Dynamic Nature

The basic feature that makes software testing different from other quality assurance methods, including inspections or static analysis, is that software testing is dynamic. Dynamic testing is the process of running the software code in a controlled environment, whereby real-time behaviour and results of the code are monitored. Testers are able to identify defects related to logic, performance, and data flow by running the application under a set of input conditions. The requirement of such dynamic help includes the possibility of evaluating the product holistically in terms of functional and non-functional requirements.

Software Inspection Concepts and Approaches

Software inspection is a means of quality assurance that examines the presence of defects within the software artifacts, with the notion that no code execution is aimed at. Inspection, unlike testing, is a process during execution, which comes as a structured, manual examination of documents such as requirements specifications, design diagrams, source code, test plans, or user manuals that deal with software. Such activity is frequently conducted in groups and in a formal way with specific assignments or roles, such as an author, moderator, reader, and reviewer, who will collaborate to identify the mistakes, discrepancies, gaps, or any deviations from standards

When to Use Software Inspection

The main goals of the software inspection are the early recognition of defects and bug prevention. Given that it can be used early in the software development life cycle (SDLC), inspections can pick up the flaws when they are still abstract and not yet coded/functional bugs, thus delivering huge savings and time costs in correcting the flaws later. As an example, a misinterpreted requirement or a buggy algorithm in a design document would cause a ripple effect of problems that would trigger a series of downstream coding and testing errors, unless discovered early during inspection.

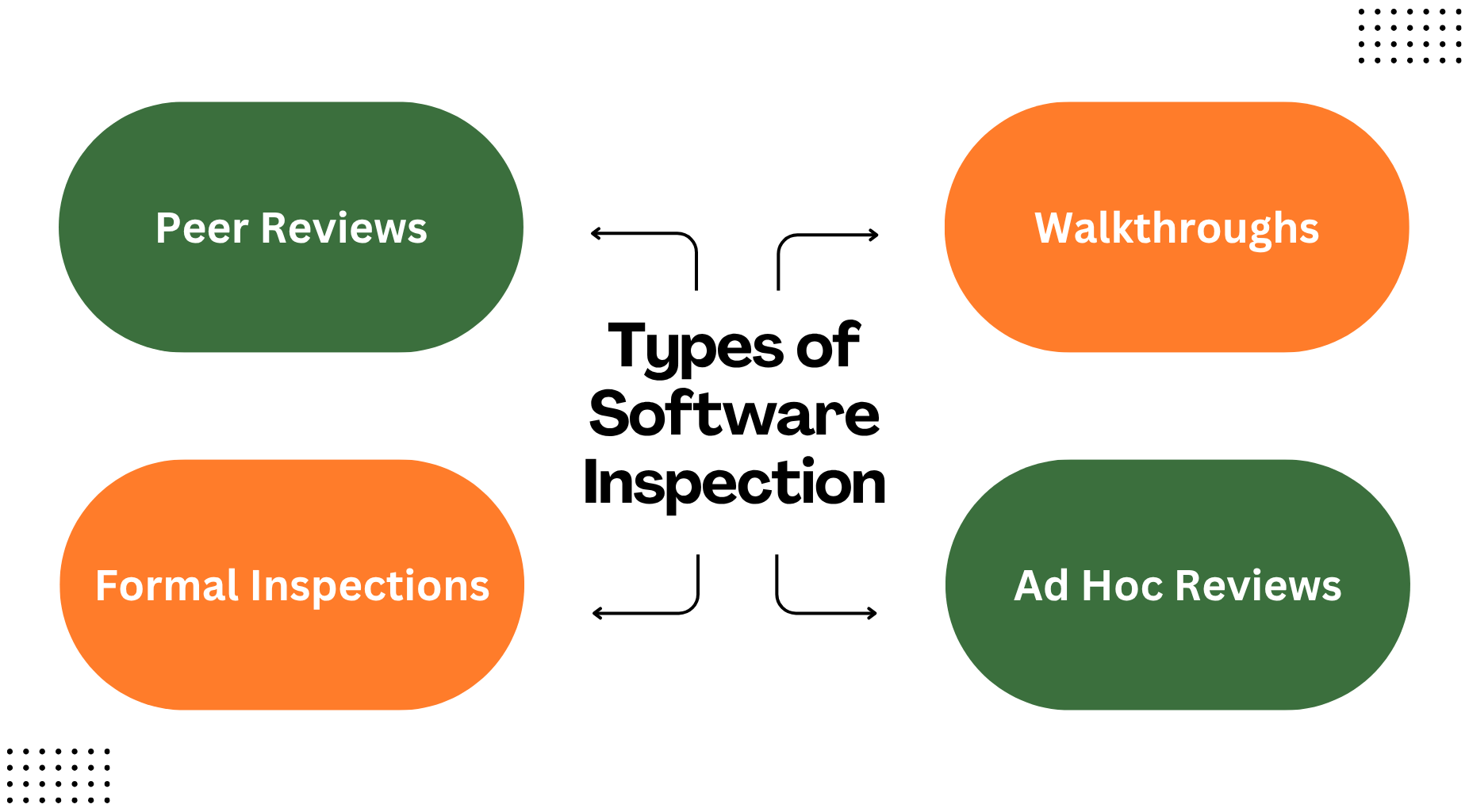

Types of Software Inspection

Software inspection refers to a variety of well-organized and semi-organized review methods that are customized to review software artifacts without executing the program. Such types can differ in terms of their formality, depth, and extent of processes involved but the common theme is the desire to identify defects early and enhance the quality of the software by using the static analysis.

Peer Reviews

Peer reviews refer to informal, or semi-formal, reviews of software artifacts that are carried out by others (colleagues) without being the original developer. They tend to be done in early-phase development (e.g., before committing a design document or piece of code). Peer review promotes ownership, teamwork, and constant feedback, and can come in the form of pairs (pair programming) or small reviews. Peer reviews are not as strict as formal inspections, but they are agile-compatible and are the best to detect easy mistakes and facilitate good coding practices.

Walkthroughs

A walkthrough is a more formal form of review and is performed by the author of the document or code under review. In a walkthrough, the author displays the work product to a team of reviewers, which more often than not could be a group of developers, testers, and business analysts. It describes the rationale, framework, or choices underlying it. This is aimed at getting feedback on who knows what and who does not, to fill any gaps of ambiguity. Walkthroughs are particularly practical in the examination of requirements documents, system architecture, and/or complicated algorithms to proceed with implementation.

Formal Inspections

The most strict and structured method of reviewing software is formal inspection. The formal inspection process was originally devised by Michael Fagan in the 1970s and consists of a specific sequence of steps, namely, plan, overview, prep, inspection gathering, rework, and follow-up. It has particular roles that include the moderator, author, reader, recorder, and reviewers. The roles of each of the participants are dependent since each member has his or her role in the introduction of the matter, finding problems, or writing a report of the defects. Regulated reviews are under the control of pre-set checklists, metrics, and entry/exit criteria. They are very useful in the identification of logic errors, non-coverage of requirements, and inconsistencies with standards, and sometimes even the flaws in organizational processes.

Ad Hoc Reviews

The least formal form of inspection is an ad hoc review, an inspection where the reviewer looks at a work product without any formal procedure or preparation. They are rapid and adaptive, but they are highly reliant on the experience and instincts of the reviewers. Ad hoc reviews are useful when checking a spot or before a first draft, but the reviews tend to be irregular, and they are unlikely to identify all the flaws as rigorously as more formal reviews.

Software Inspection is of a Static Nature

One major unique feature of software inspection is that it is a ‘non-testing’ practice in the sense that no actual running of the software code is needed in a software inspection. Rather than executing the program, the process of inspection aims at checking software artifacts described as requirement specifications, the design documents, architectural models, source code, interface definitions, or even test plans. This can help teams to nullify the defects even before the software is compiled or deployed, thus minimizing the total cost as well as the efforts incurred in the correction of defects. Since no runtime environment is required, inspection can occur early in the development cycle and perhaps even pre-executable code.

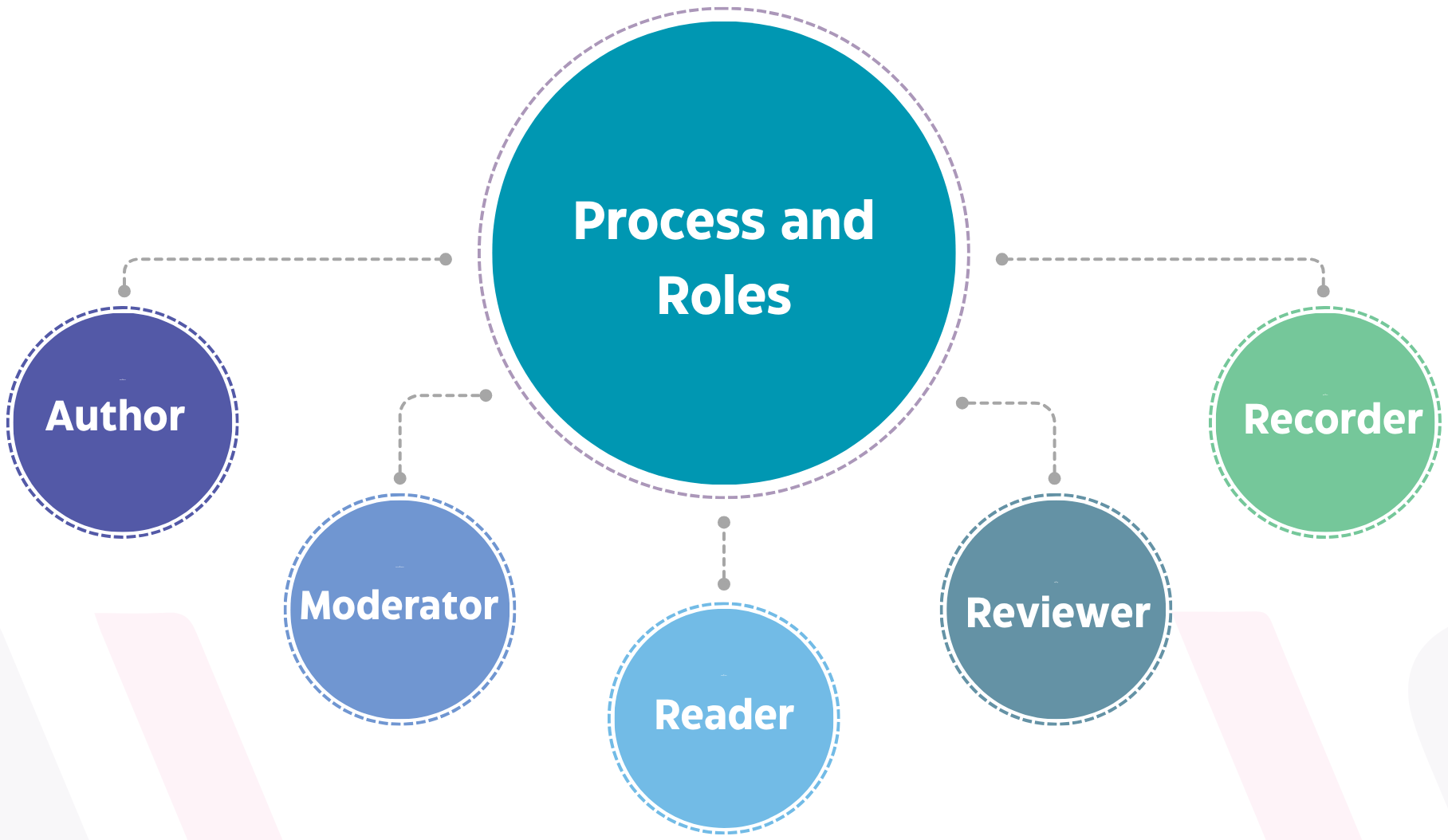

Process and Roles

One of the strongest features of software inspection is that it is a methodical and position-oriented procedure, as this can facilitate the inspection handsomely in that it can lead to care, responsibility, and cooperation. Formal inspections have a workflow as compared to informal reviews and usually entail steps like planning, preparation, meeting for inspection, and rework, in addition to follow-up, among others. All the stages are also performed by the team members with certain roles, so that every element of the artifact can be critically discussed.

- Author: The Author describes the individual who made the document or code under inspection. They are supposed to be able to explain any inquiry and have remedies for any defects identified by the inspection team.

- Moderator: It is the moderator who judges on whether or not the artifact is ready to undergo inspection and whether it is good enough to be admitted.

- Reader: The inspection meeting is done under supervision of the Reader who will paraphrase or read one line or one section at a time. This will allow all the participants to have the same understanding of the material under review and will give the session a logical progression.

- Reviewer: The reviewers are the team members who make the prior preparations in advance to scrutinize the artifact against errors, inconsistencies, or deviations. They come with a critical eye, and they tend to use checklists to inform their inspection. Depending on the artifact being reviewed, the reviewers can be developers, testers, business analysts, or knowledgeable about the domain.

- Recorder: The Recorder (or Scribe) records the faults, problems, and discussion items revealed by the inspection. This makes a complete record that cannot be lost or forgotten, and hence can form a permanent record that can be used to track defect trends or process improvement.

Software Testing vs. Software Inspection: Detailed Analysis

Software inspection and software testing are different yet complementary activities in software quality control. Fundamentally, they are different in their nature: Testing is a dynamic process where we execute the code, whilst inspection is an exercise that is static and considers only that which can be analysed manually and not the running code. Such distinction greatly influences the time and manner of each of them in the software development life cycle (SDLC).

Let’s look at a detailed comparison between testing and inspection.

| Aspect | Software Testing | Software Inspection |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | An active process of executing software with real data to find defects and verify functionality. | A static process of examining software artifacts (requirements, design, code) to identify defects without executing the program. |

| Objective | To verify and validate that the software meets functional and non-functional requirements. | To detect defects early in documentation or code before execution. |

| Execution Requirement | Requires running the code in a controlled environment. | No code execution is required; it involves review and analysis only. |

| Timing in SDLC | Performed after implementation, typically during and after coding phases. | Performed early in SDLC, during requirements and design phases. |

| Type of Activity | Dynamic quality assurance method. | Static quality assurance method. |

| Nature of Detection | Finds run-time errors like crashes, memory leaks, or incorrect outputs. | Finds logical errors, inconsistencies, and non-adherence to standards. |

| Cost of Defect Fix | Higher, as defects are found later in the cycle. | Lower, as defects are caught early before code execution. |

| Involvement | Usually performed by QA/Testers, sometimes with developer support. | Typically involves peer reviews with developers, architects, or QA leads. |

| Outcome | Confirms software behavior and performance under real conditions. | Confirms software artifacts’ correctness and adherence to design/standards. |

| Examples | Unit testing, integration testing, system testing, and acceptance testing. | Requirement review, design inspection, code review, and test plan inspection. |

Software testing and software inspection complement each other in ensuring high-quality software. Testing validates the actual behavior of the running application, while inspection detects defects early in the development cycle without code execution. Using both methods together creates a multi-layered quality assurance approach that reduces risks, saves costs, and ensures reliable software delivery.

Conclusion

Software testing and software inspection serve as two complementary pillars of software quality assurance. Testing actively validates software functionality through execution, identifying runtime errors and ensuring the product performs as expected under real-world conditions. Inspection, on the other hand, is a static and preventive process that uncovers defects early in documentation and design, significantly reducing the cost of fixing errors.

Together, these approaches create a robust quality framework, enabling organizations to deliver reliable, efficient, and high-performing software that meets both business and user expectations.

| Achieve More Than 90% Test Automation | |

| Step by Step Walkthroughs and Help | |

| 14 Day Free Trial, Cancel Anytime |