Software Requirements Guide: BRS vs. SRS vs. FRS

|

|

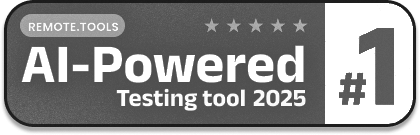

The story of every software product that went on to succeed and make its mark doesn’t start from the day you wrote your very first line of code. It starts with documentation, not just any documentation, but a disciplined document that explains what we are trying to build, why it matters, and how we expect the code to behave. In the realm of software engineering, these three papers are what is known as the cycle of understanding. They are:

- Business Requirements Specification (BRS)

- Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

- Functional Requirements Specification (FRS)

While they may be conceptually and practically aligned, there are differences in what needs to be done during the conversion of this high-level business need into a concrete system that is testable. They collectively serve as a business vision-to-technical execution bridge, ensuring all parties (stakeholders-developers-testers) are aligned. Yet, confusion persists.

Many organizations mix up these documents and tend to use them on each other instead of overlapping them, or even lack one of these levels, which causes massive ineffective communication, unrealistic expectations, and rework costs. In this article, we will explore the specifics of each document, what they contain, who is responsible for them, how they evolve, and how all these things come together to form the basis of any successful software delivery process.

| Key Takeaways: |

|---|

|

The Foundation of Requirements Documentation

The software requirements document is not a piece of paper, but rather, one’s declaration of intent. It connects the customer vision and the engineering plan. Let’s understand first why we have different types of documentation, and then move to find the difference between BRS, SRS, and FRS. Every paper is a level of translation:

- The BRS identifies the business problem and objectives using the customer’s language.

- The SRS converts that into technical goals and limits that are perceived by engineering teams.

- The FRS explains the functional behavior of the system, which is what the system is expected to do.

This top-down work is going to ensure that all the stakeholders, devs, and QA are operating under a single agreed purpose and scope. Ambiguity can flourish in the absence of that. Teams chase assumptions, developers implement functionality that is not the core business need, and someone tests something that behaves differently than expected. Hence, requirements documentation is not bureaucracy; it is the framework of understanding.

Business Requirements Specification (BRS)

In the hierarchy of software requirements, the top layer is Business Requirement Specification. It represents the desired outcomes of the business and its motivations. This is a way of expressing the project that is more about business deliverables than implementation.

A BRS is goal-based, object-oriented, scope-oriented, and high-level-focused in the sense that it does not elaborate on how the goals are to be satisfied. A business analyst typically creates it in collaboration with stakeholders, product owners, and customers.

Let’s consider an example. When an organization plans to develop an e-commerce site, the BRS can contain statements like:

- The system should enable customers to order products online.

- The system should allow customers to track their orders and receive real-time shipment updates.

- The system must support various currencies.

- The system should provide secure online payment options, including credit cards, debit cards, and digital wallets.

- The objective is to increase online sales by 40 percent within one year.

These are business-oriented statements, representing needs and success criteria that are strategically focused.

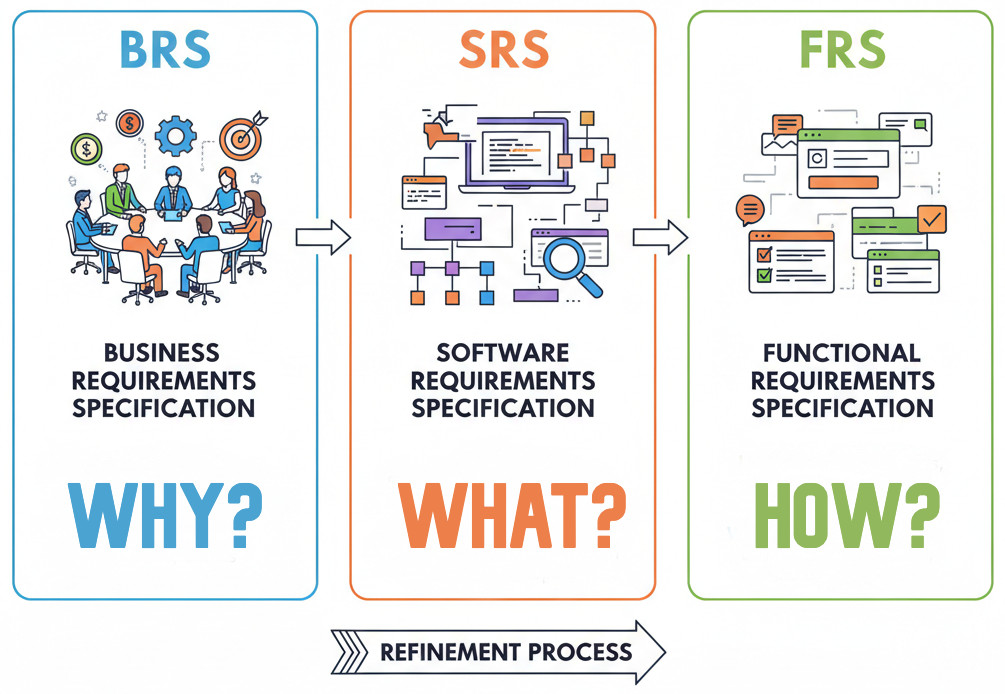

The Structure of a BRS

A Business Requirement Specification (BRS) is a formal package that states the project’s needs in a structured format. So that it is easier for all parties (business owners, users, and developers) to understand and review the project needs. It serves as a blueprint that augments the business vision and exhibits how a project is to be accomplished in order for everyone working on it to share a common understanding of what the project will deliver. A typical comprehensive BRS consists of:

- Business Goals: These are top-level vision and mission goals for the business that you want to achieve through this effort. They articulate the reasons for and outcomes that define strategic success for a project.

- Project Scope: This is where you explain what your project will and will not cover. It heads off scope creep by setting clear boundaries and delivery expectations.

- Stakeholder Analysis: It names all players, including those who have influence over, approve of, or benefit from the project. Understanding stakeholder roles will help ensure that their needs are met and that you stay informed throughout the lifecycle.

- Business Requirements: These are the primary requirements, issues to address, or opportunities the project is intended to achieve. They distill from those goals the actionable needs that will inform design and development.

- Success Criteria: These are measurable signs that determine at what point the project has succeeded in achieving its objectives. They offer a measurable method to evaluate performance and check whether you have achieved your business goals.

- Top-level Constraints: This part describes the primary constraints that could impact the project, including time, cost, regulation, and market forces. The sooner one acknowledges these limitations, the better for planning and risk management.

Ownership and Audience

The business side typically owns the BRS, comprising business analysts, product managers, or customers. It’s a bridge, or a communication channel (or whatever you want to call it), from management to the development team, and before any technical design is created, there is always an agreement.

It is the “why” document that explains – why the project exists.

Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

The BRS tells us what the point of having a project is, and the Software Requirements Specification(SRS) specifies what should be done by the system in order to achieve that purpose. Software Requirements Specification is a detailed technical version of business requirements (or other source document, e.g, Use case) translated into functional and non-functional requirements organized in a manner to be understandable by all stakeholders. It is the primary reference point for developers, architects, testers, and operations, meaning everyone knows exactly how the system should act in order to achieve business goals.

An SRS is not about user stories or UI details. It does not specify how the system will be implemented; rather, it describes a level of performance expected from the system and all logical flows, data exchanges, load factors, required response times, and also the fulfillment rate of external system interactions. It is the ‘technical arm’ of the work unit, keeping in touch with what was defined in the BRS while developing. As an example, based on the previous e-commerce example, the SRS may comprise:

- The system will enable a user to create an account via email or social account.

- The system will facilitate the search of the catalog in terms of keywords or categories.

- The system should be able to handle 100,000 simultaneous transactions.

- The system shall send order confirmation and tracking details to the customer’s registered email address.

- The system shall ensure that all customer data is stored securely in compliance with data protection regulations such as GDPR. Read: AI Compliance for Software.

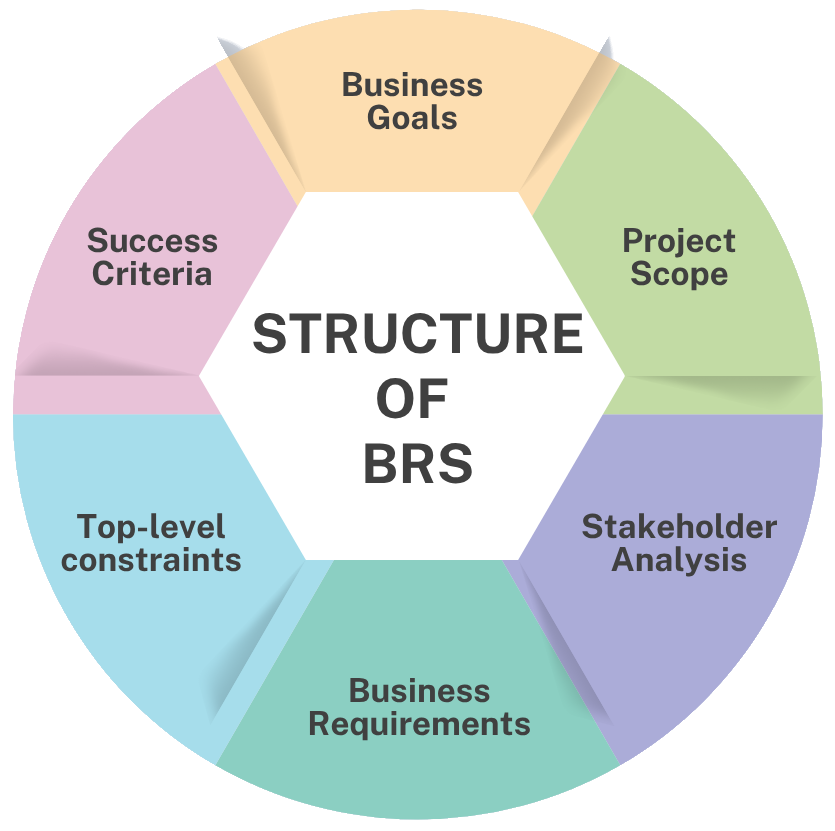

The Structure of an SRS

An SRS is a comprehensive description of what the software should do, how it will function, and how it will be used. It turns business intent into an implemented, technical plan. Everyone (devs, testers) can work together with a shared understanding of what the system does. Qualities of a good SRS: An effective SRS offers dependability, traceability, and completeness at all points in the development process.

An SRS includes:

- Purpose and Scope: This section gives fine-grained meaning to the business objectives specified in the BRS and relates them to individual system goals. It describes in no uncertain terms what the software will do and where its intended scope ends.

- System Overview: This explains how the solution fits within a business and technical landscape. It provides readers with an overview of where the system fits within their current processes, technologies, and environments.

- Functional Requirements: These define what the system is supposed to do, be like, and how it should work to satisfy business needs. They describe what the system ought to do, that is, actions, inputs, outputs, and user interactions.

- Non-Functional Requirements: These specify the quality features based on which the performance, security, reliability, and scalability of the system are described. It serves that the system not just works, but performs optimally and robustly under varying conditions. Read more about Functional Testing and Non-functional Testing – What’s the Difference?

- Interfaces: They detail how the system interacts with other systems, applications, or APIs. This comprises exchange protocols, data abstraction methods, and integration demands for transparent interoperability.

- Data Requirements: These describe the data structures, flow, and storage of information that are needed for system operation. It may contain schema definitions or database design guidelines, and data integrity or privacy concerns. Read more about Test Data Generation Automation.

- Limitations and Assumptions: This part enumerates environmental, technical, or legal constraints that can influence design and development. It also captures planning assumptions, which can assist stakeholders in managing risk and making informed expectations.

Ownership and Role

The system is owned by the technical and engineering community, normally written by a system analyst or solution architect. BRS is about values, and SRS is about the logic of a system. It makes certain that every feature links back to a business objective- tracking strategy and execution. An SRS is the document that development, integration, and testing guys follow. It is also a form of change management, with baseline and verification in the successive lifecycle.

Functional Requirements Specification (FRS)

If the SRS tells you what a system is supposed to do, then a Functional Requirements Specification (FRS) focuses still further down to how the system should behave from an end-user perspective. Roughly, it translates the SRS into a structured and detailed list of correct, unambiguous, and implementable functions that have been fully thought through. For the record, whereas SRS tells what is to be done, FRS states how it is to be done as per the user overview.

The FRS will usually include elaborate workflows, UI interactions, validation rules, and screen behaviors. It helps keep documentation of every awesome feature clear, concise, and testable. Why? So that developers can accurately deliver the features while testers can validate them properly. In the case of our e-commerce, the FRS may consist of:

- Upon clicking the ‘Add to Cart’ button, the system is supposed to save the chosen item, along with its quantity and price, in a temporary session.

- In case of a payment failure, the system should show an error message and record the occurrence.

- The user profile page must be able to update personal information with field-level validation.

- Upon completing an order, the system shall send a confirmation email to the customer with the order ID, payment summary, and estimated delivery date.

- The system shall generate an order summary showing item details, taxes, discounts, and delivery timelines after successful checkout.

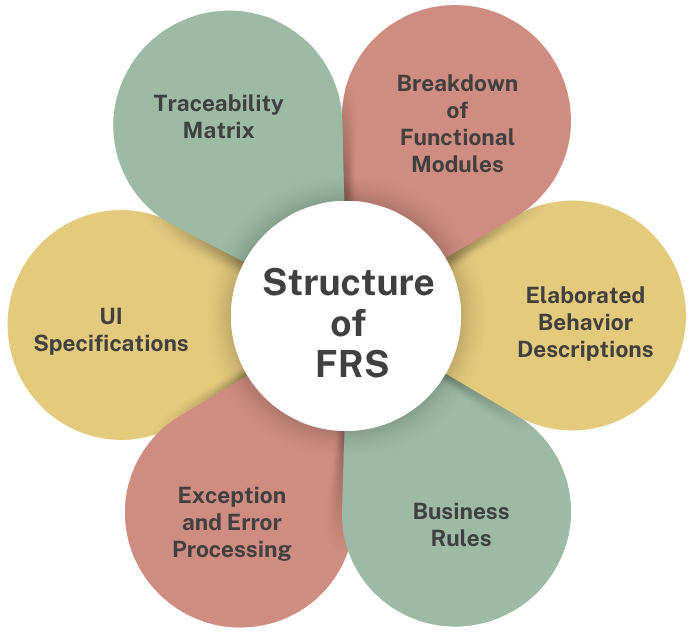

The Structure of an FRS

A Functional Requirements Specification is a detailed, step-by-step description of how a system will behave from the perspective of the user. It breaks down the SRS’s high-level features into fine-grained testable functions and cases. A well-defined FRS makes sure that the developers, testers, and designers have the same understanding of all aspects of the system to be developed. A typical FRS contains:

- Breakdown of Functional Modules: This section organizes the system into logical modules, such as checkout, user profile, or search, to simplify understanding and implementation. Grouping functions into modules helps manage complexity and ensures consistent behavior across related features.

- Elaborated Behavior Descriptions: Here, each function is explained in detail, including inputs and outputs, as well as triggers, and expected responses for the system. This allows workflows to be unambiguously defined, and user and system behavior to be predicted.

- Business Rules: They are the focal points of business specifications that outline the logic and execution conditions determining system operation. They guarantee that all functions of the company comply with company policies, procedures, and regulations.

- Exception and Error Processing: This section describes the system behavior in the event of failures or exceptional cases. It goes a long way to make your app robust, as you can have predictable recovery systems and friendlier error messages.

- UI Specifications: Visual and functional information on how users will use the system is provided in UI specifications. This includes headers, field descriptions, navigation flow, and interface behavior based on each action.

- Traceability Matrix: The traceability matrix correlates every function in the FRS with its respective objects in the BRS and SRS documents. This will provide end-to-end visibility, responsibility, and sign off on completeness in addressing both business and system requirements.

Ownership and Collaboration

FRS is generally co-authored by the business analysts, system engineers, and QA team. It is the most tangible evidence of developers and testers. For testers, FRS is priceless. It tells them how they’re meant to act for verification. To implementers, it is a design document used to decide on the logic of implementation.

BRS vs. SRS vs. FRS

The BRS, SRS, and FRS are a hierarchy of tiers from business intent to technical implementation. The following table provides at a glance differences in purpose, ownership, detail, and focus for each document that jointly lead to 100% alignment from vision to actualization.

| BRS (Business Requirements Specification) | SRS (Software Requirements Specification) | FRS (Functional Requirements Specification) |

|---|---|---|

| Defines why the project is being undertaken — the business goals and expected outcomes. | Defines what the system should do to meet business requirements. | Defines how the system will behave and interact from a user’s perspective. |

| Focuses on business objectives, needs, and success criteria. | Focuses on system functionality, features, and constraints. | Focuses on detailed functional behavior, workflows, and user interactions. |

| Intended for business stakeholders, clients, and product owners. | Intended for developers, architects, testers, and project managers. | Intended for developers, UI/UX designers, and QA testers. |

| Owned by business analysts, product managers, or clients. | Owned by system analysts or solution architects. | Owned by functional analysts or development leads. |

| Contains high-level business goals, scope, stakeholders, and success metrics. | Contains detailed functional and non-functional system requirements. | Contains functional modules, business rules, UI behaviors, and validation logic. |

| Written in business-friendly, non-technical language. | Written in semi-technical language, bridging business and technical teams. | Written in technical and functional language, focusing on executable details. |

| Provides a high-level overview without implementation details. | Provides mid-level technical detail defining system expectations. | Provides low-level detail specifying exact user and system actions. |

| Changes rarely and reflects long-term business direction. | Changes moderately as requirements evolve. | Changes frequently with functional or design updates. |

| Produces business objectives and measurable goals. | Produces a system design and development blueprint. | Produces functional workflows and testable behaviors. |

| Ensures business alignment — solving the right problem. | Ensures technical alignment — meeting defined requirements. | Ensures quality alignment — verifying expected functionality. |

Mapping the Journey

To see the relation of these articles, think of concepts to code as a sequence of translations.

- BRS → Business goals and needs.

- SRS → Technical translation of such objectives to system-level requirements.

- FRS → Functional breakdown of the system into actions that can be executed.

This stratified flow is a way of ensuring that all the technical decisions have a business reason behind them. It offers a rational sequence of responsibility that harmonizes teams and reduces misunderstanding.

An Example:

Imagine that a firm requires a system that will automate insurance claims processing.

- BRS: The system will allow users to submit claims online and decrease claim settlement time by 30 percent.

- SRS: The system will have user registration, claim submission, claim verification, and payment tracking modules.

- FRS: Once a user makes a claim, the system will real-time validate policy information through an external API and alert the claim officer to review the claim.

The intent is translated into more specificity in each layer. The BRS explains why, the SRS explains what, and the FRS explains how.

The Importance of Alignment

In most companies, there’s a documentation gap between business, engineering, and QA. What these gaps yield is the production of misaligned outputs; what was produced did not correspond to what was expected. With a clear order of BRS to SRS to FRS, it is possible to align on three planes:

- Business Alignment: The solution directly resolves the business problem and intentions of the project.

- Technical Alignment: Validates that architecture and design are consistent with system requirements.

- Quality Alignment: Assumes that test cases are actually verifying solutions for the intended functionality and performance.

All documents are each other’s mirror image for traceability and accountability. These consistencies are particularly important in Agile and DevOps, where swiftness might even outrun clarity. In the iterative model, these BRS, SRS, and FRS are still necessary, and those requirements are now outlined in user stories and acceptance criteria.

The Relationship with QA and Testing

To quality teams, BRS, SRS, and FRS are not documentation, but the basis of the test strategy.

- Under the BRS, testers gain insight into the business impacts of defects.

- They determine system-level testing requirements, which are performance, integration, and security, based on the SRS.

- They obtain functional and regression test cases of the FRS.

Intelligent AI-powered testing platforms, such as testRigor, further leverage this relationship. testRigor can read plain English Functional Requirement Specifications (FRS) and turn them into actual test cases, all on its own. This allows each and every function described in the documentation to be accurately verified against the running application, thus bridging the gap between documentation and test automation. Read more about Natural Language Processing for Software Testing.

Achieving Documentation Excellence

Great documentation makes certain that all the needs, from business vision to functional execution, are clear, in sync, and up to date. It fills communication gaps between teams, avoids expensive misconceptions, and encourages continuous alignment over the course of a project. The following are the principles that underlie the need to maintain precision, cooperation, and flexibility in requirement writing.

- Start with Clarity: The best requirements documents aren’t written to be impressive; they’re written to be clear. Simplicity, consistency, and traceability matter much more than verbosity.

- Ensure Bidirectional Traceability: Every BRS point should be connected to one or more points in SRS, and every SRS item should connect with FRS. Further, we will move to the test cases. This ensures that validation is conducted end-to-end (and makes it easy to analyze the impact of changes).

- Collaborate Across Functions: Such documents should be reviewed and co-authored by business analysts, architects, developers, and testers. Common ownership means there are no blind spots and everything is a starting point.

- Leverage AI for Maintenance: AI tools can now dissect requirement documents for contradictions, inconsistencies or voids. They can collate changes across BRS, SRS, and FRS layers – ensuring that dynamic projects stay in tune.

Conclusion

BRS, SRS, and FRS are not mere documents; it is the lifeblood of alignment that brings together vision (Why), design (What), and execution/compliance (How) in software development. Collectively, they transform abstract business intentions into executable, testable, and observable results, becoming the bridge between idea and artifact. In an era of automation, AI, and DevOps, the clarity provided by these documents becomes the driving force behind the development of intelligent software that works efficiently for you.